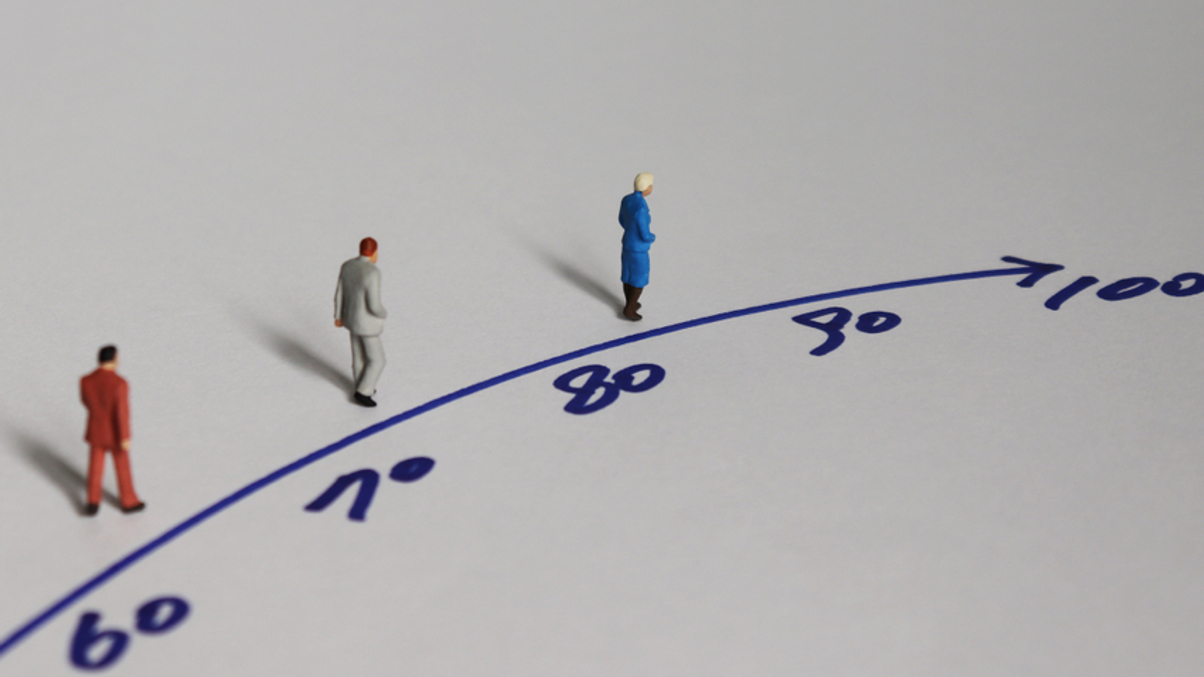

Overhauling Japan’s pensions system

Japan’s retirement system is in need of drastic change, but is the gradual shift to defined-contribution plans just a cop out?

The Japanese pension system is in need of change. Given the size and sophistication of the country, Japan ranks a lowly 31 out of 37 on the Melbourne Mercer Global Pension Index (MMGPI), a gauge of how well a developed market's pension system is geared to meeting long-term needs.

Sign in to read on!

Registered users get 2 free articles in 30 days.

Subscribers have full unlimited access to AsianInvestor

Not signed up? New users get 2 free articles per month, plus a 7-day unlimited free trial.

¬ Haymarket Media Limited. All rights reserved.