Ex-BoJ official says JGB safety “relative”

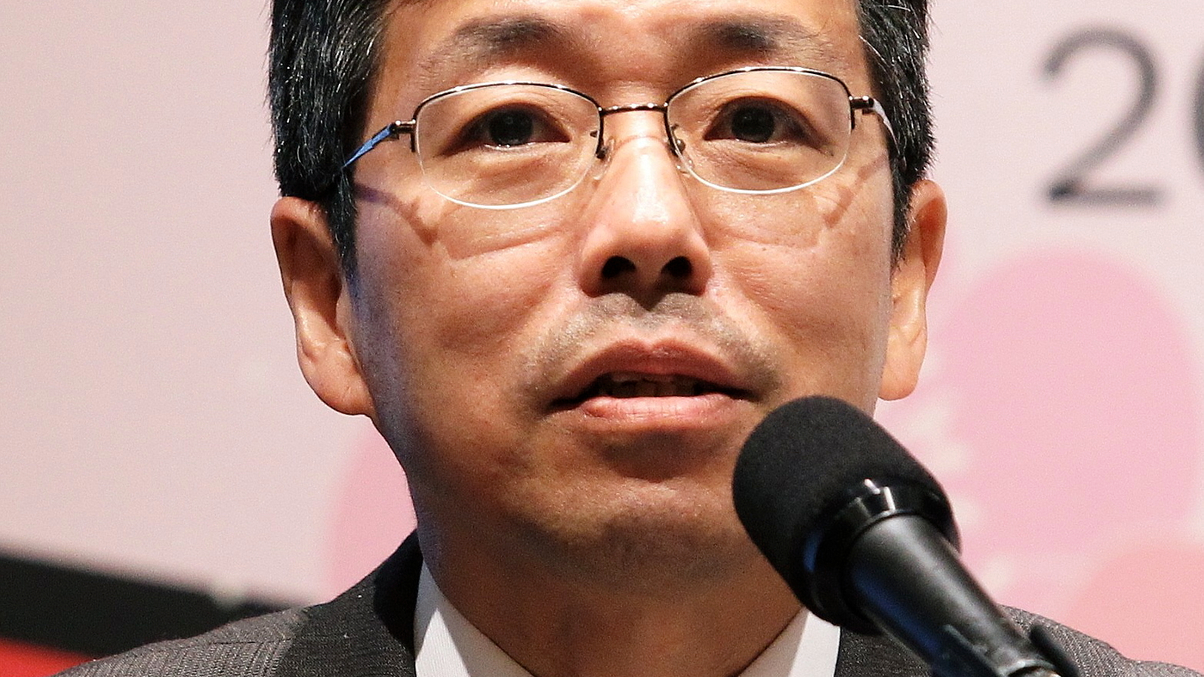

Nobusuke Tamaki, a former official at Bank of Japan and Government Investment Pension Fund, says government bonds may not be as safe as believed.

Nobusuke Tamaki delivered a speech at a recent conference in Tokyo organised by AsianInvestor in which he warned the audience of pension funds and investment professionals that Japanese government bonds’ “risk-free” image was a matter of perception.

Sign in to read on!

Registered users get 2 free articles in 30 days.

Subscribers have full unlimited access to AsianInvestor

Not signed up? New users get 2 free articles per month, plus a 7-day unlimited free trial.

¬ Haymarket Media Limited. All rights reserved.