Tabung Haji seeks to diversify but fights shy of risky assets

The RM82.64 billion ($20.6 billion) Malaysian Hajj fund, which recently completed a restructure, is looking to diversify globally but remains cautious of risky assets.

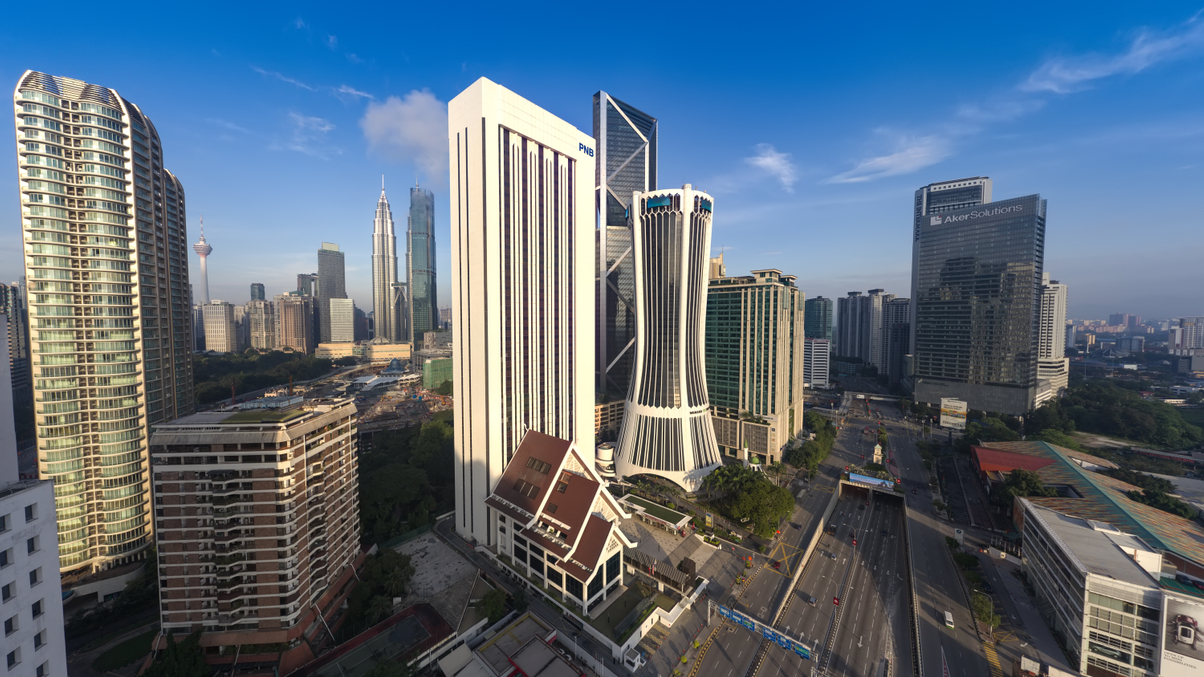

Malaysia’s Hajj fund Tabung Haji (TH) is looking to diversify away from Asia Pacific ex-Japan markets into global markets in order to diversify and capture higher risk-adjusted returns, says its executive director of investment Mohamad Damshal Awang Damit.

Sign in to read on!

Registered users get 2 free articles in 30 days.

Subscribers have full unlimited access to AsianInvestor

Not signed up? New users get 2 free articles per month, plus a 7-day unlimited free trial.

¬ Haymarket Media Limited. All rights reserved.